Journal 1 November 2018

The School of Traditional Arts Heads to China

The Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts has been assisting conservationists in China to revive the treasures of the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang

Set in the vast windswept expanse of the Gobi Desert, the Chinese city of Dunhuang is modestly sized but boasts huge historical importance. A major commercial hub along the ancient Silk Road that linked China with Europe, the city saw traders, travellers and strings of caravans stop over to refuel after passing through a particularly arduous stretch of sand. With silk heading west and wool, silver and gold heading east along this 4,000-mile trading route, Dunhuang became a centre for cultural and intellectual exchange, as wandering monks brought Buddhism from India to new territories.

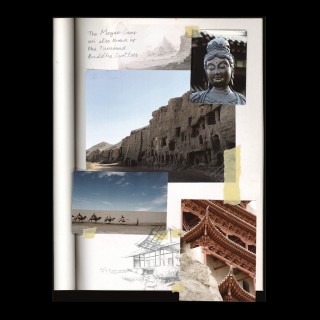

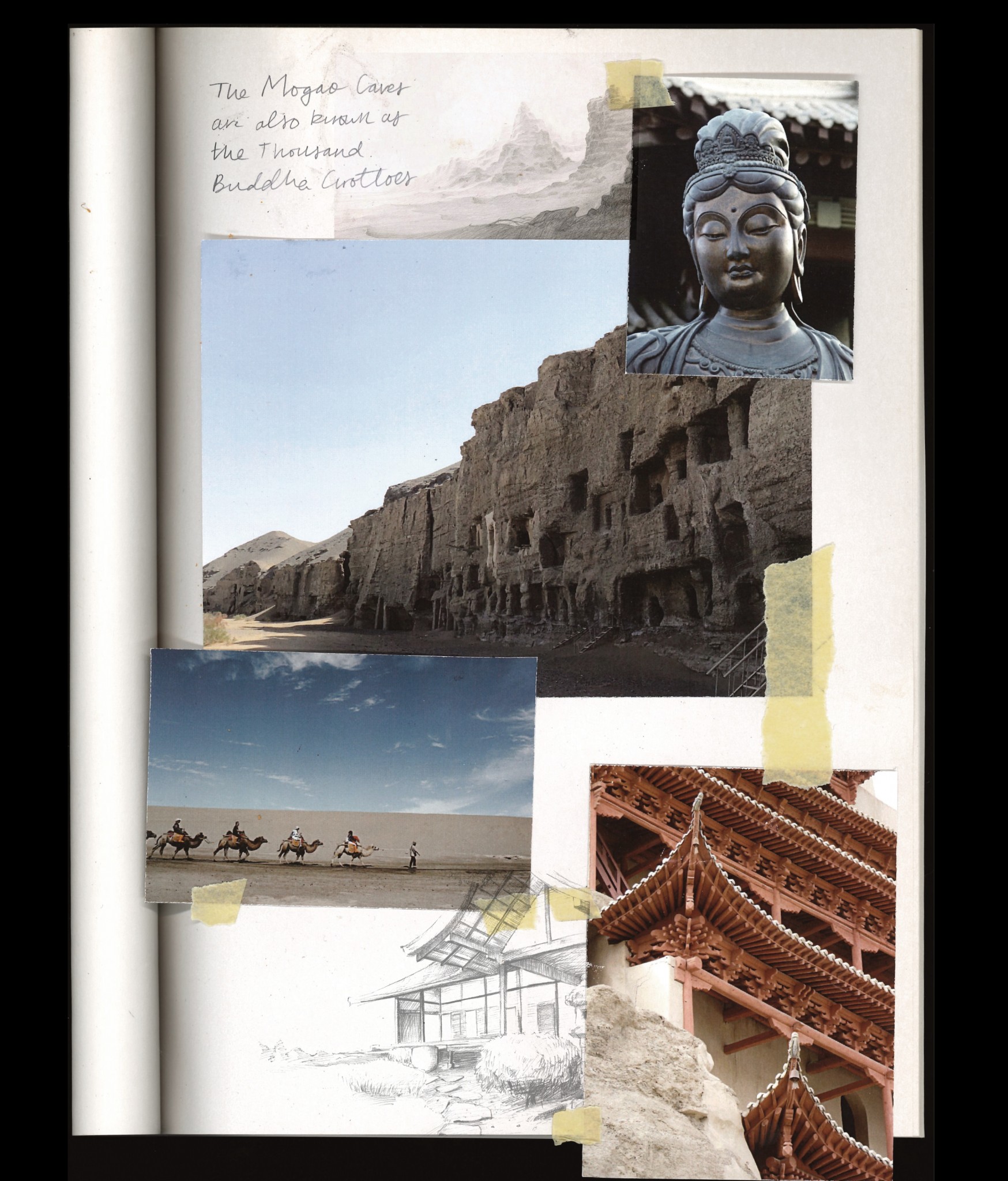

It was these Buddhist monks who carved an extensive series of caves into the sandstone cliffs in the fourth century. A day’s walk from Dunhuang, the Mogao Caves, awarded Unesco World Heritage status in 1987, are recognised as one of the world’s most important sites for Buddhist art, there are 492 caves as well as temples and angular stupas – which mark the tombs of monks – scattered across the desert landscape. The sprawling series of decorated caves house artwork spanning many artistic mediums, including apsarasas (flying celestial beings) on the walls, sculptures of fierce temple guardians and bodhisattvas, as well as geometric panels, textiles, wood carvings and 45,000 square metres of murals. A major rediscovery of manuscripts and artefacts in 1900 have added further to its historical importance and – despite their remote location – the caves attract up to 6,000 tourists each day.

To help protect, manage and understand the caves, the Dunhuang Research Academy (DRA) was set up in 1943 to oversee a generation-spanning range of projects that include measuring and documenting the murals, conserving the caves and sharing these findings with the world. Building on a collaboration with the DRA that began in 2015, the Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts (PFSTA) set up an exchange programme last year, sending five artists (all School PhD alumni) to Dunhuang to share their expertise in the use of pigments with the research team. Through workshops, talks, studio demonstrations and visits to the caves, the artists would collaborate with a group of researchers in Dunhuang – who are also practising artists – to restore and replicate the murals. The resulting sharing of knowledge was intended to assist and inspire this DRA team in its future work, both in the caves and in their independent projects.

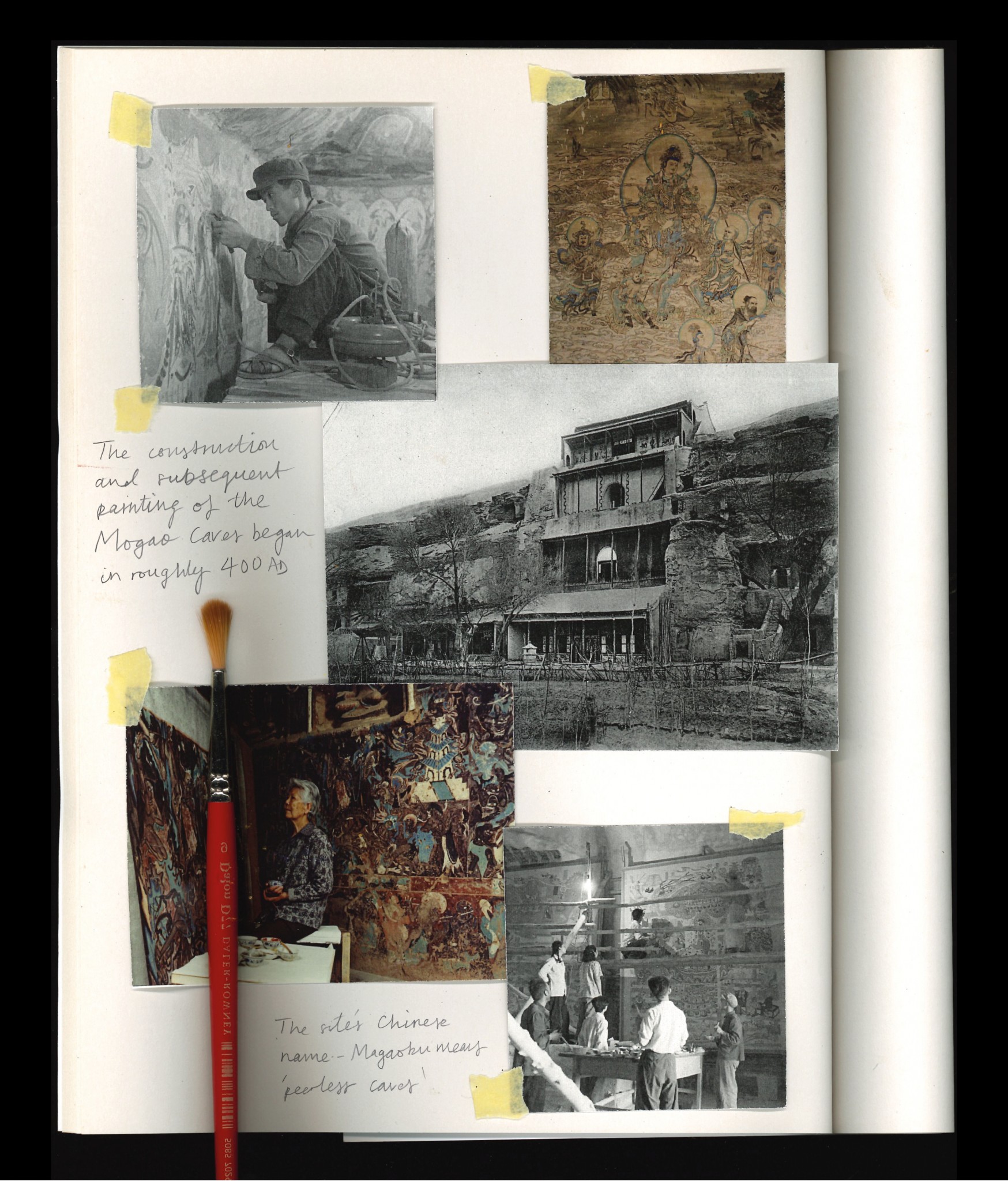

For David Cranswick, an artist with expertise in the painting materials and techniques used by artists between the 13th and 18th centuries, the opportunity to share information and creative experience with professional artists made the exchange an intriguing proposition. He was there to guide workshops on preparing pigments from nature using plants, rocks, earth and bones, and was impressed by the talent of the Dunhuang artists. “Their understanding of technique excels anything I have seen in the west, with a freshness and vitality that is so badly needed in the art world,” he says. “Seeing these artists work shows so clearly what we have lost in our art education, which has abandoned any training in technique.”

Another of the visiting artists was PFSTA alumnus and artist Desmond Lazaro – an expert in the art of Indian miniature painting. After spending 12 years in Rajasthan as an apprenticed temple painter in the Pichhwai tradition, Lazaro’s interest in Dunhuang lay in its influence on contemporary art in India today and the story of how Buddhism moved from India to China. “If you were to regard India as the parent culture, with painting methods and materials originating there, you can find references to Dunhuang in the Ajanta Caves in Maharashtra, India, which predate Dunhuang by a couple of centuries,” says Lazaro. “And because of the situation in China for the past 50 years or so, this [exchange] was a way for the Chinese artists to learn more about the parent civilisation.”

Lazaro had known about the caves for many years but this was his first opportunity to visit. “I’d always wanted to go to China because if you look at miniature painting there is a crossover between China and India. With paper coming from China, ink coming from the Middle East and the movement of both towards India led to miniature painting in northern India, so it’s always interesting to find out about the roots of that.”

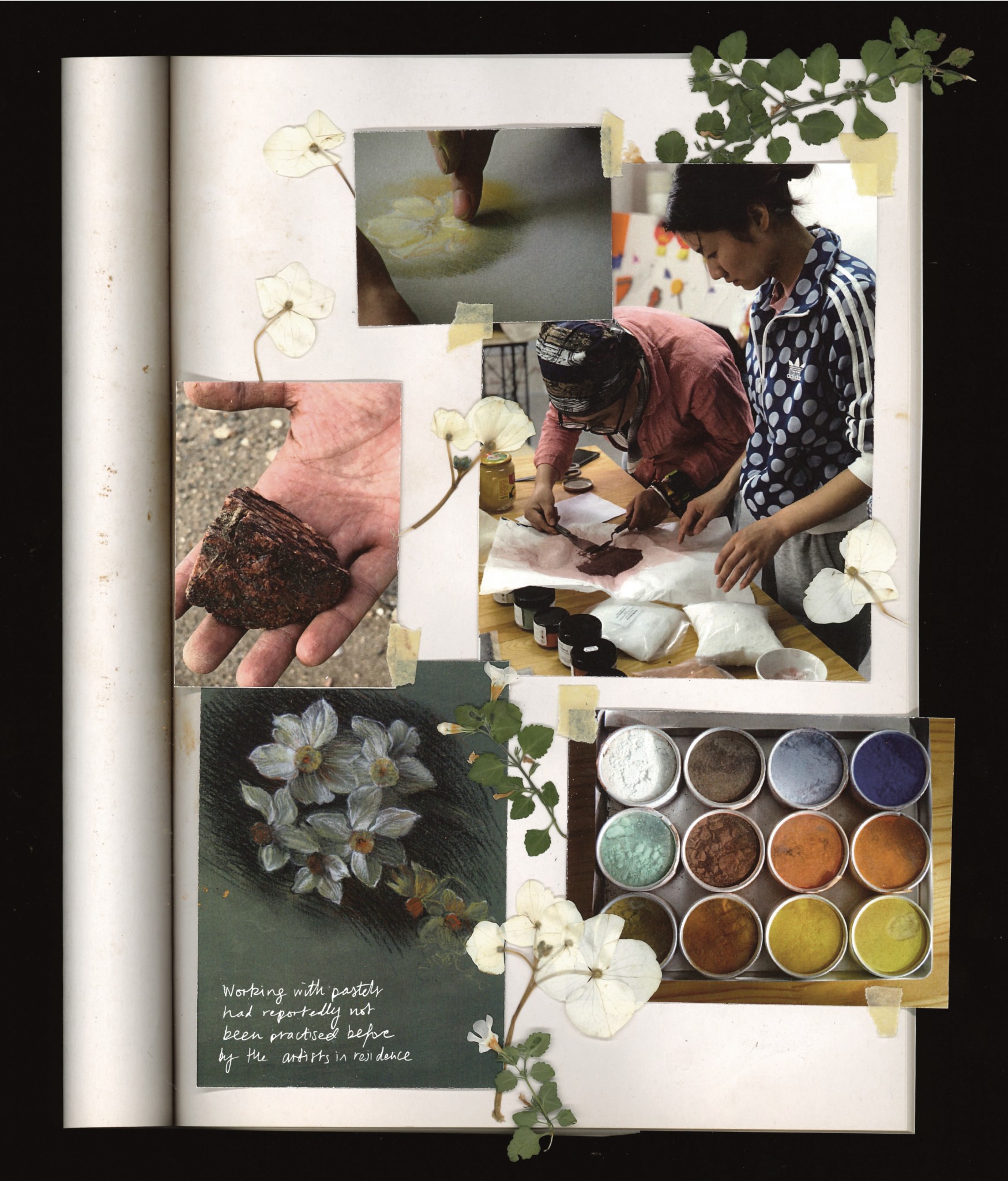

In Dunhuang, Lazaro’s workshops saw an emphasis on scaling down the work of the DRA artists, equipping them with smaller brushes and encouraging a more contemplative practice. “If you’re working on a wall there’s only a certain amount of delicacy you can achieve, but on paper you have to condense everything down to tiny meditative brush strokes,” he says. “Allowing the painting process to be a form of meditation helped to reconnect them to a source of where this work would have come from.”

Bringing expertise in early modern and modern western European drawing, Romanian artist Dr Radu Leon was chosen to show the Dunhuang artists a different way of working directly with pigment. Having immersed himself in all he could learn from the British Library and British Museum prior to his visit, Leon’s trip saw him arrive in April 2018 as Dunhuang was coming into bloom. “It opened up all sort of sensorial gates ahead of spring,” he says. “Because part of my subject matter was floral painting, it was very timely.”

Through his workshops, Leon was also able to introduce some new practices to the artists at the DRA. “Working in pastels, as well as painting en plein-air, had reportedly not been attempted before by the artists in residence,” he says. “It’s a great addition to their existing skills because it changes routine. Sometimes we focus overly on details because you want to respect a tradition and want to stay within the footsteps of your predecessors meaning it’s hard to take five steps back.”

Leon’s workshops explored the parallels between Dunhuang and Venice as centres of cultural and religious crossover and the use of pure pigment in pastel form, which were carried out between his own trips to the caves. What he found particularly striking was the dialogue between the caves’ interiors and exteriors. “When you’re looking at the murals inside the cave and you turn to the source of light you see the desert – there was a connection between how people see the desert now and how other people saw it in the past.” He also found visual links in some of the Chinese Buddhist paintings – flowers, folds, hand gestures – that brought back memories of early modern Romanian frescoes and Venetian ornaments. “After two days exploring the caves I was exhausted, knowing there were so many more caves – it makes you realise the amount of work that the DRA is doing to preserve and to share that knowledge and beauty with others.”

The preservation of the Mogao Caves remains a key concern for the DRA as they balance protecting them with promoting their cultural value. “The Mogao caves have been declining for more than 1,000 years and are very vulnerable now,” says Ma Jinhui, an artist at the DRA. “It is threatened by oxidation and weathering and since the caves are made of earth and clay, they won’t last forever. Visits by a large amount of tourists will inevitably cause harm to it – we have to protect the Mogao Caves and show them to the world at the same time.” Huang Liufang, Resident Artist at the DRA’s Fine Art Department says the challenges of restoration extend beyond technical know-how. “It’s also linked to education and the aesthetic appreciation of the Mogao Caves at a spiritual level,” he says. “I hope that there will be further interactive communications and sustainable long-term programmes between the DRA and PFSTA and other professional collaborations, so as to accumulate more practical experience.” Dr Lazaro has already taken steps to continue his work with the DRA, triggered by the sight of a mural in one of the caves depicting the relationship between a water deity, a monk and a mysterious monkey god. “I’m hoping this work might lead to an exhibition exploring the role of the South Indian deity Hanuman and the Monk King,” he says. Meanwhile Leon touched upon the spirit of the exchange by recounting a memorable final night in Dunhuang. “Drinking hot, salted milk tea in a Mongol tent on our last evening, we talked about art and life and we realised that we shared something: a sense of communion among us and with nature and a wish to communicate the beauty of it to others.”

With this assembly of artistic talent from the Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts helping to foster a reciprocation of skills and knowledge between the east and west, the beauty of the Mogao Caves appears in good shape to inspire future generations of artists, too.