Journal 18 February 2020

The importance of preserving heritage crafts

Is craft renaissance a reality and what can the next generation expect from a profession that favours patience and precision over turning a fast profit?

At a highly choreographed event at London’s Design Museum in May, Dame Helen Mirren unveiled the winner of this year’s Loewe Craft Prize. Supported by the revered Spanish fashion house, this glitzy occasion brought together 30 craftsmen and women from around the world, spanning ceramics, jewellery, textiles, woodwork, glass and metalwork, with Scottish ceramicist Jennifer Lee winning the award for her curvaceous hand-coiled vase featuring oxidised pigments.

Woodcarving / Sarah Goss:

Woodcarving is used to create ornamentation including architectural embellishments and reliefs. The scrolled corbel bracket pictured was hand-carved into an acanthus leaf design

Woodcarving / Sarah Goss:

Woodcarving is used to create ornamentation including architectural embellishments and reliefs. The scrolled corbel bracket pictured was hand-carved into an acanthus leaf design

An increasingly tangible makers’ movement has contributed to the impression of a recent craft revival. Fashion brands are incorporating craft elements and influences into couture collections, ideas of process and provenance are key concerns for any new product launch while city-wide celebrations, such as spring’s London Craft Week, are forging new communities among makers, creatives, enthusiasts and consumers. Its potential for individualisation, environmental sustainability and ethical production has forced craft onto political agendas, too.

Yet below the surface, this positivity isn’t always evident. Figures show a large drop last year in the number of students taking art and design GCSEs – a worrying trend that has continued for the past five years. Elsewhere, the scarcity of apprenticeships, the length of training needed to achieve proficiency and a lack of awareness of career options prevent students taking craft skills into the workplace. The Radcliffe Red List of Endangered Crafts, published by the Heritage Crafts Association, has identified more than 20 craft skills that are either extinct or critically endangered.

Nurturing a new generation of makers is essential for the proliferation of craft, with a need for adequate training, support and role models to encourage those with a desire to learn. Could more be done to preserve yesterday’s skills for tomorrow? And just how relevant is craft in 2018? We spoke to four prominent figures from the world of craft – Deyan Sudjic, director of the London Design Museum, which hosted the Loewe Craft Prize; Simon Sadinsky, Deputy Executive Director of Education at The Prince’s Foundation; Sarah Goss, woodcarver; and Simon Trethewey, Director of Studies, MA Programme, at The Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts – for their thoughts.

Bookbinding / Gillian Stewart:

The codex format of bookbinding, which involves pressing and sewing individual or concertinaed pages together, dates back

to the Romans

Bookbinding / Gillian Stewart:

The codex format of bookbinding, which involves pressing and sewing individual or concertinaed pages together, dates back

to the Romans

What makes craft so important in 2018?

Deyan Sudjic: We live in a world in which the digital explosion has made so many categories of objects redundant. These are things that once had a role that went far beyond utility. They were the possessions that we used to embody memories, to mark the essential landmarks of life, to show something about who we are. As we used them and lived with them, they marked the passing of time. A smart phone is not much compensation for a wristwatch inherited from a parent, or a pen worn smooth with use. Humans are still hardwired to look for the consolations of tactile qualities. The crafted object continues to give us so many of those things.

Simon Sadinksky: Craft is about connection – to nature, to one’s place and to oneself. It is about connecting the past to the present, while looking towards the future. A good example of this is that there are more than six million pre-1919 buildings in the UK requiring specialist skills to repair and maintain. Without training the next generation of craftspeople, we are at risk of losing some of our most important built heritage.

Sarah Goss: We are surrounded by mass-produced items, with the focus on production being quick and cheap to ensure the maximum profit for the people at the top. I think there is a growing number of people that would like to go back to having items that are handmade, with unique characteristics and a story behind them. Items crafted the traditional way provide a link back to how our ancestors made things and this is appealing to a lot of people.

Why has craft come under threat?

Simon Trethewey: The past 200 years have seen the rise of the machine, which can make things infinitely faster and cheaper, meaning craft doesn’t stand a chance. There’s also the philosophical threat of the marketplace. To paraphrase Brian Keeble, author of Art For Whom and For What?, the question we have to ask is not “What does a man get for his work?” but “What does he get by working?”.

DS: People have been talking about the meaning of art, craft and design since the time of Ruskin and Morris. It is a less prominent part of the conversation now. Survival is perhaps the key driver. A gallery introduces a different element into the relationship between the maker and their audience – or should we say user, or even client or collector.

*SS:*A significant proportion of those working in the sector are approaching retirement and many are not currently undertaking activities to pass along their skills, either due to a perceived lack of opportunity or the practicality of balancing the running of a small business with a dedication to training. There is also an ongoing challenge of encouraging the younger generation to see traditional crafts as a viable path – which it is – and one that can provide a varied, stimulating and rewarding career.

SG: Cheap imports, even if handmade items rather than factory produced, will still undercut us significantly. We just can’t compete with those sort of prices. I think it’s incredibly important to make sure children have access to craft and art-type subjects in school. Practical skills are so vital and I feel these are being put to the bottom of the list of priorities in favour of computer-based studies. Even if children aren’t overly fond of a particular craft to take up as a career, they will learn useful skills as a by-product, such as hand-eye coordination and design concepts. We seem to be getting to a point where kids can write code but they don’t know how to thread a needle or put up a shelf.

Are we witnessing a craft revival?

SS: We are certainly noticing increasing demand in our craft training programmes, both from applicants and from craftspeople and companies who take our students on placement. I think there is more value placed on working with your hands, in practical training and in reconnecting with the craft traditions of the place you inhabit. There also seems to be an increasing focus on sustainability and the role craft plays within this area.

ST: The young are certainly more concerned with the ecological state of the world and there’s a resolve to redress the situation we find ourselves in.

SS: We are also finding an increasing number of people moving to craft after careers in a different profession. While this is positive, it is important that we provide entry ways from an earlier age to ensure those interested are not pushed in other directions.

SG: I think there has been an increasing interest in going back to traditional methods in many industries. I get the impression that while there is still a market for flatpack furniture (limited disposable incomes will always ensure there is a market for budget-friendly items) people are now looking for pieces that are a little bit different and reflect the years of skill that have to be gained to make these items. Personalised presents seem to have taken off in the past few years as well – if you can have something hand carved with a name and date, it makes it so much more special. My customers like the idea of having something unique to pass down through generations to come. In a time when we are constantly bombarded with things we can buy, having something that’s not off-the-shelf is becoming more important.

Basket Weaving / Annemarie O'Sullivan: Basket weaving dates back many thousands of years. The kindling basket pictured is made from hazel, gathered in the spring and woven the following winter

Basket Weaving / Annemarie O'Sullivan: Basket weaving dates back many thousands of years. The kindling basket pictured is made from hazel, gathered in the spring and woven the following winter

Could more be done to promote craft?

SS: It is important that schools see craft as a viable, skilled and impactful career and a valid alternative to what may be considered more mainstream careers. We often hear from participants in our programmes – particularly those approaching craft as a second career – that they were pushed towards university, despite an interest in and aptitude for working with their hands.

DS: Why is the idea of the hand quite so important? There is huge skill in the workforce at McLaren, who pattern-cut fibreglass components for car bodies like dress makers, just as Azzedine Alaïa’s garments show skill, technique and design.

SS: I think there is a perhaps stereotyped representation of the careers available. It is important that craft is promoted from an early age, meaning that exposure to and experience in these skills are provided from school onwards.

*SG:*Craft could be made more accessible by having more ‘have-a-go’ courses where you don’t have to commit to a 10-week course for example. Workshops like those available at London Craft Week where people can come along and try things out, rather than just watching someone else do it. Keep the crafts going in schools, if kids have grown up around traditional tools and methods they’re not going to fear taking it up again when they grow up.

How can we best preserve crafts for the next generation?

SS: he provision of suitable training routes is vitally important – it is a diverse field and there must be a variety of educational pathways available that are flexible, supportive and innovative. The link between theory and practice is an important one, with strong links between practitioners, students and sector organisations crucial to not only encouraging but facilitating the next generation to take up traditional crafts.

ST: Understanding that the learning process is a spiritual development rather than something to make a living by, although hopefully the two can be integrated. Craft can satisfy the very urge that the machine age and materialisation can’t – the joy is in the person who makes the original rather than the one who presses the button to replicate it.

DS: The Design Museum was very glad to work with the Loewe Foundation on staging the exhibition of the 30 Craft Prize finalists for their award. They all saw the importance of having their work shown in the context of a wider discussion of how design plays a part in our culture. It showed its beauty and its relevance.

SG: By instilling in our children the value of working hard and learning a skill. By doing this they will then have a better understanding of the value and the time that has gone into making handmade pieces and will treasure them as much as we do. In my experience it does seem to be that the older you get the more interested in history – particularly your own history – you are. How your ancestors lived and worked has a certain fascination and by maintaining traditional crafts you’re continuing this invisible thread that links you to your predecessors.

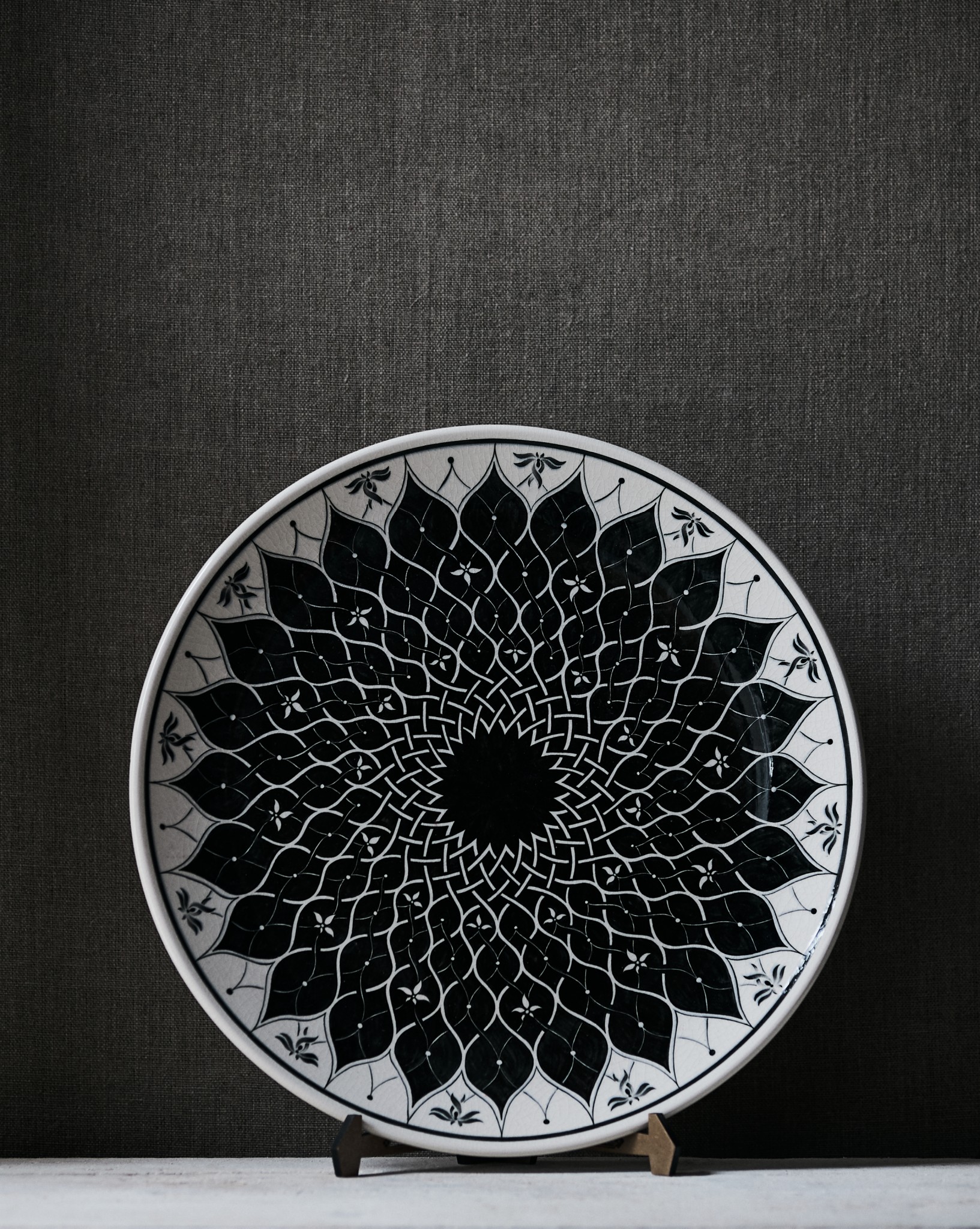

Ceramics / Sabbiha Khankishiyeva:

Ceramics transforms raw materials into fine objects through clay preparation, shaping and design. The decorative plate pictured fuses contemporary paintwork with

historic references

Ceramics / Sabbiha Khankishiyeva:

Ceramics transforms raw materials into fine objects through clay preparation, shaping and design. The decorative plate pictured fuses contemporary paintwork with

historic references

What advice would you give young makers?

SS: To remember the opportunities and challenges they were presented with when honing their craft and to use their experiences to train those who will follow them. When we deliver our programmes, we firmly believe that we are training not just the next generation of master craftspeople but the next generation of tutors. They should be encouraged to make their voices heard; to encourage, inspire and educate.

ST: Craft is quite literally a spiritual journey that can lead to the development of skills, confidence and the joy of being someone who can create. It’s very tempting to see craft as a skill and skill alone, after which you go out and get a job. In fact, to engage in a craft is to take on a practice and a lifelong journey.

SG: Don’t give up if you haven’t mastered a craft after a couple of years. If you go into almost any practical skill you must be prepared to play the long game. Part of the appeal of carving to me is that I will never stop learning, there will always be something that I can improve on. It’s taken me the best part of 10 years of carving to get to where I am now and there are still many areas of my work that I need to work on. Most master carvers have been carving for 20 to 30 years; learning a skill doesn’t happen overnight and in a generation where instant gratification is becoming the norm, I worry that the next generation won’t have the patience. I hope they prove me wrong!

Woman in craft

Lily Marsh’s career path seemed destined to lead to a desk, until she discovered stonemasonry

Lily Marsh had hoped for a creative career but, unsure of her options, settled for a desk-based job. Then inspiration struck: “I first became aware of stonemasonry while watching a TV programme featuring stonemasons carving gargoyles at Gloucester Cathedral,” she recalls. “I contacted the Building Crafts College in London – a specialist college teaching building crafts and construction. Looking around the workshops and talking to the tutors about how I could train was like a light switching on in my head. I felt such relief this existed as a career.”

Lily graduated with an advanced diploma in stonemasonry from the Building Crafts College. Next she attended The Prince’s Foundation’s Building Crafts Programme, acquiring an NVQ Level 3 qualification, and a variety of on-site experience. “Being able to try different crafts during the Summer School opened my eyes to the wider heritage craft industry and stonemasonry’s place within it,” she says.

As for gender equality in stonemasonry, Lily says it’s a mixed bag. “On the whole I’ve had a positive experience. There are skilled stonemasons working who are women and, in my mind, I don’t feel it’s surprising in the craft industry any more,” she says. “But I’ve had experiences to challenge that. I’ve had angry reactions from other tradespeople who don’t think I should be working in a manual job. Seeing more women skilfully working in manual, heavy lifting jobs would be helpful in challenging narrow assumptions about what people are capable of.”

Lily’s advice for anyone interested in stonemasonry is to give it a go. “It’s a rewarding way to work creatively and learn traditional heritage skills, as well as connecting with your built environment,” she says.