Journal 19 November 2018

Understanding food provenance

An awareness of the negative effects of industrial farming, the return of traditional agriculture and a growing preference for seasonal, sustainable produce, could help us rethink the way we eat: the future of food is on our hands.

We live in a fast-paced world that demands quick, convenient, cheap food. Globally, the majority of us do not know where our food comes from, nor do we seem to understand the damage the current industrialised food system is doing to us and the environment. Large-scale farming and pesticide use decimates the land; we’re left without insects, wildlife, or farmworkers. We’re left instead with tasteless, nutrition-bereft produce and a system of agriculture that’s impossible to support. The cost to our wellbeing is immeasurable. Food has to sustain us, in more ways that one. So how do we reverse the process?

Supporting ‘slow food’, reconnecting with food that’s good for us, good for the people who grow it and good for the planet is seen as the antithesis to the negative impact of large-scale agriculture. And it’s a call to arms for many chefs, farmers and food writers. “It’s important to have a connection with the food you eat,” reiterated Melissa Hemsley at this August’s Eat Happy Summer Supper event held at Dumfries House. The best-selling food writer and slow-food advocate was on hand to officially launch the Scottish Organic and Sustainable Food and Drink Festival which will take place on the Estate next year. “England and Scotland are farming countries, and we’ve got to honour these people who – day in, day out – grow our food. Food is nutrition; it’s our all-round physicality and mental health.” Next summer’s event aims to do just that. Festival goers will sample food and drink from across the country, interact with chefs and producers through cookery demonstrations and masterclasses, and be part of the development of Dumfries House’s existing commitment to organic food.

The Estate itself is well on the way to organic certification. An announcement in January brought news that the Kauffman Education Gardens at the House – where each year thousands of schoolchildren learn about tending to, preparing and cooking vegetables – had received official organic certification from the Soil Association, with the nearby 2,000 acre Home Farm set to follow suit in early 2019. “Organic gardening creates a healthy living soil, and organic methods are important factors in food security and people’s health,” explains Education Gardener, Chris Jones. “Organic farming espouses the highest standards of animal welfare, reduces our exposure to pesticides, supports more wildlife and offsets greenhouse gases. If you follow the standards and best practice, when you finish with your garden or farm, you should leave it in better condition for future generations.”

Once considered fringe concerns, seasonality, sustainability and low-intervention methods for cultivating the land are now far more common, and the organic market is growing at pace. Figures show that sales of organic food in Scotland grew by nearly 20 per cent in 2017, something that Isla McCulloch, business development manager at Soil Association Scotland, puts down to increased recognition of its benefits. “Public awareness of what organic really means – for health and for the environment – has never been higher,” she says.

To help farmers tap into what has become a £2 billion market, the Scottish government is encouraging applications for organic conversion funding, while the Soil Association continues to support farmers looking to make the transition. On a local level, there are initiatives sprouting up across the country, including the Locavore vegetable box scheme, based in Glasgow; shops selling locally grown and artisanal wares, such as the award-winning Loch Arthur Farm Shop in Beeswing and the Gosford Bothy Farm Shop run by third-generation farmers; and larger initiatives including Farming for a Better Climate, which helps farmers increase profitability and reduce their carbon footprint. The Prince’s Foundation’s dedication to organic certification is an assured step in the right direction.

Restaurants are also rising to the occasion. The rewards reaped by choosing local produce are best witnessed in the success of farm-to-fork cuisine in Scotland’s leading restaurants, including three ventures overseen by The Prince’s Foundation. “Local is key to my day-to-day,” says the head chef at the Rothesay Rooms in Ballater, Ross Cochrane. Initially launched as a pop-up last year by HRH The Prince of Wales, to attract tourists after the devastation caused by Storm Frank, the award-winning restaurant is now a permanent fixture. “My suppliers tell me what’s available,” says Cochrane, who also set up The Carriage, the just-launched bistro, café and tea room in Ballater’s historic Old Royal Station. “We serve local produce on our menus, which change every six to eight weeks, and I personally visit each farm before creating new dishes. It’s very rewarding to know my ingredients come from within 20 miles – the only real challenge I have is deciding what I’m going to do with all the fantastic produce!”

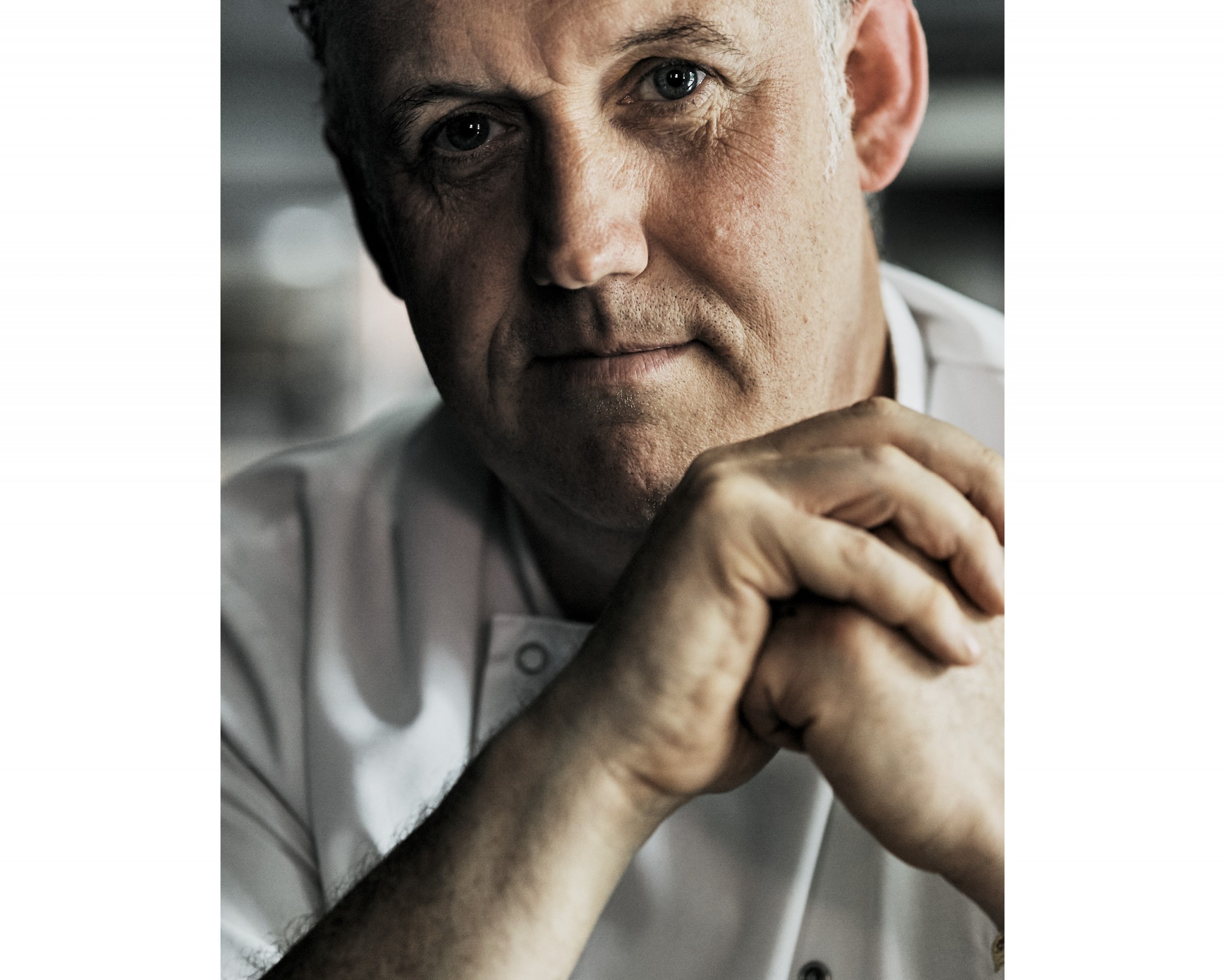

Championing local suppliers is also key at Dumfries House’s own Woodlands Restaurant. “In keeping with the Foundation’s ethos, we source as much as we can locally,” says head chef Adam McKissock. Ayrshire born and bred, McKissock worked at award-winning restaurants and hotels in Glasgow, as well as London’s Michelin-starred Hotel Café Royal, before returning to Scotland and taking the reins at Woodlands nearly five years ago. “Our fish supplier is from Troon, we get meat from one of our tenant farmers, who is also our main butcher. We also have some roe deer from the Estate, and we use as much as possible from our organic and walled gardens, while the rest is from a supplier in Prestwick. We get our salmon and trout smoked on demand from a smokehouse in a small town called Fairlie, North Ayrshire.”

This focus on the quality and provenance of produce – both in restaurants and at home – will help to foster a healthier and more conscious relationship with food, and according to Hemsley, that can only be a good thing. “We are so far removed from the farm element of food these days that we are unhappier around mealtimes,” she says. “So often we’re too busy to prioritise good food, and lose the connection you get from cooking, pulling things out of the fridge and microwaving them instead. If we can start to rethink the hours in our day and make time to prepare something simple and quick, we can re-form that connection.”